Oklahoma state ban on abortion, one of the toughest in the nation

OKLAHOMA CITY (AP) — With Oklahoma only days away from enacting the toughest state ban on abortion in the U.S., providers were preparing to stop terminating pregnancies as questions remained Friday about enforcing the law’s limited exceptions.

The law allows abortions to save a pregnant patient’s life “in a medical emergency” and supporters said doctors still would decide what an emergency is, though that could change later if it becomes perceived as a loophole. There’s also an exception for cases of rape, sexual assault or incest that have been reported to law enforcement, but it doesn’t help victims who don’t report the crimes to police.

Abortion providers said they are likely to be cautious because the new law, like a ban at about six weeks enacted earlier and a similar 2021 law in Texas, will expose them to potentially expensive lawsuits over alleged violations. They’re planning to refer some patients to states like Colorado or Kansas, but some won’t be able to manage the extra time or travel involved.

Oklahoma will provide a preview of what is in store for other states if the U.S. Supreme Court follows through on a draft opinion leaked earlier this month overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. The law also is likely to prompt Oklahoma residents — and Texans who’d traveled to the neighboring state — to go elsewhere to end their pregnancies.

“An abortion ban in one state doesn’t stay just in that state,” said Neta Meltzer, a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood Rocky Mountains, which operates two dozen health centers in Colorado and New Mexico. “It absolutely has ripple effects in neighboring states and across the country.”

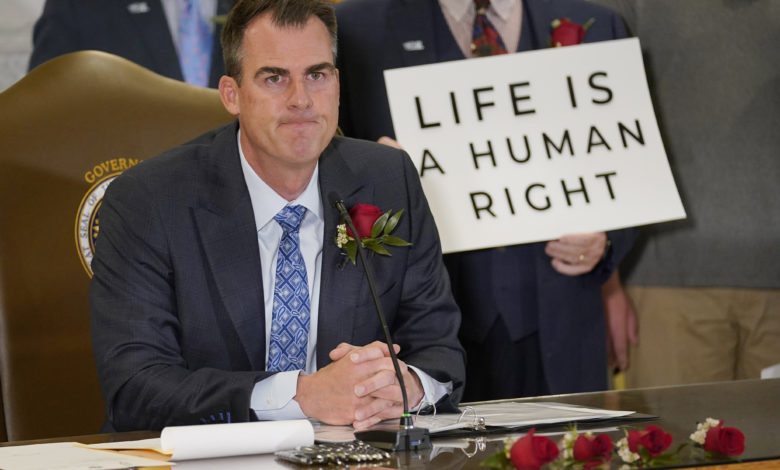

The Republican-dominated Oklahoma Legislature approved the abortion ban Thursday, and GOP Gov. Kevin Stitt, a strong abortion foe, is expected to sign it once it reaches his desk, probably early next week. The bill contains a clause that says it takes effect as soon as he does.

“All of our rights end when we do harm to someone else, and we believe strongly that the life of the unborn child is a life that deserves protection,” said the Oklahoma Senate’s top leader, Greg Treat, an Oklahoma City Republican. “If we have to pay an economic price for that, I’m willing to pay an economic price for that.”

The two Planned Parenthood clinics in Oklahoma, in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, suspended abortion services after Stitt signed the six-week ban earlier this month. A clinic run by Trust Women in Oklahoma City is providing abortion services until Stitt signs the new law. An attorney for the Tulsa Women’s Clinic said it would also stop performing abortions as soon as the law is signed.

Abortion rights advocates hope to challenge the new law in state courts, despite a provision saying that no court has the authority to issue an order blocking the law temporarily in response to such a challenge.

Even if a challenge were successful, Rabia Muqaddam, a senior Center for Reproductive Rights attorney said, “It may be some time and the results will just continue to be catastrophic for patients.”

The push for the law is part of a larger effort to restrict or ban abortion in Republican-led states, anticipating a U.S. Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe. About two dozen states are poised to ban abortion.

But because Oklahoma moved first toward a ban beginning at the “fusion” of sperm and egg, the White House labeled it the most extreme anti-abortion measure so far.

Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said in a statement: “In addition, it adopts Texas’ absurd plan to allow private citizens to sue their neighbors for providing reproductive health care and helping women to exercise their constitutional rights.”

Katy Gluck, a 39-year-old health care worker from the Oklahoma City area, joined a group of about a half dozen protesters Friday at the Capitol as they chanted, “My body, my choice” in the rotunda.

“Do I agree in late-term abortions? No, I don’t,” she said. But, she added, “the government should have no say in what we do with our bodies. It’s just an attack on women, and I don’t agree with it.”

Both supporters and critics of the new law agreed that the threat of civil lawsuits, which could be filed up to six years after an abortion, and fines of up to $10,000 are powerful incentives for providers to avoid running afoul of it.

Another Oklahoma law, signed by Stitt in April and set to take effect in August, will make it a felony to perform an abortion, punishable by up to 10 years in prison and a fine of up to $100,000. It is being challenged in state district court.

“Ultimately, a lot of this is going to come down to a risk assessment by each abortion provider to decide what level of risk they’re able to take on,” said Jessica Arons, a senior American Civil Liberties Union attorney on abortion issues.

Part of the risk for abortion providers is parsing out how the new law’s limited exceptions apply.

The exception allowing abortions to save a pregnant person’s life doesn’t specify who has the final say on what constitutes a medical emergency, but Treat and other supporters said doctors still will be empowered to make those decisions. State Rep. Wendi Stearman, the new law’s author, said such abortions would be done in hospitals.

“I would like to be able to trust our doctors in this state to know when it is necessary to perform an abortion, and there are cases when it is,” said Stearman, a Tulsa-area Republican.

But Mallory Schwarz, executive director of Pro-Choice Missouri, suggested such an exemption is “hollow,” saying such language requires the patient “to basically be on their deathbed.”

“If they’re not sick enough yet, then they might not qualify for that medical emergency,” Schwarz said. “If they’re not on their deathbed, is it an emergency?”

Supporters said requiring victims of rape, sexual assault and incest to report the crimes to law enforcement means there is a record to rely upon. The law doesn’t specify that a written report is required.

Abortion opponents acknowledged struggling with including the exception because they believe, as Stitt said in a Fox News interview Sunday, “that is a human being inside the womb.” Stearman said she included it in the new law so that a rapist or family member committing incest wouldn’t be able to file a lawsuit over an abortion.

But providers and abortion rights advocates said requiring the crimes to be reported to allow an abortion likely means that most victims won’t be able to obtain abortions. Victims have a variety of reasons for not reporting, including fear of retaliation or because they believe police won’t act.

And, said Jessie Hill, a law professor at Case Western University in Cleveland, “Is there any clear way to basically say we think women are going to lie about being assaulted?”

“I don’t think they’ve thought through any of this,” said Hill, an attorney in challenges to abortion laws in Ohio. “I’m not sure they even know how any of it works, honestly.”

Treat said the new law will work “in concert” with others already on the books.

“We have been very thoughtful on these, sought legal counsel, and got feedback,” he said.

Meanwhile, clinics in other states are bracing for an influx of patients from Oklahoma.

In Shreveport, Louisiana, Administrator Kathaleen Pittman was helping answer the phone at the Hope Medical Group for Women because of the high volume of calls.

She and her employees put patients on a waiting list, calling them back for appointments weeks out. The clinic is doing its work under the shadow of Louisiana’s 2006 “trigger” law that will ban abortion if Roe v. Wade is overturned. Her clinic and two others in the state would close, she said.

“Can you imagine how confusing it is for the public?” she said.